PETER MORVILLE

We are sure glad that Peter happened upon the book, Careers in Library Science, one day whilst wondering around a library. This podcast walks through how he got started in Information Architecture and began to create a connection between the physical organization of library information and the online world. In fact, this connection ultimately lead to the famous “Polar Bear Book,” by Peter and Louis Rosenfeld called Information Architecture for the World Wide Web published by O’Reilly.

HIGHLIGHTS WITH TIMECODES

- 5:24 Argus Associates

- 7:00 The birth of the Polar Bear Book

- 7:40 The pain with no name

- 8:55 How to reframe the problem

- 11:53 Library of Congress

- 17:30 Information Literacy

LET’S TALK

What do you think? Do you agree or disagree with the author? What inspired you from this episode? What did you learn? What resources were most helpful? Please add a comment and share your thoughts with us!

HERE’S THE FULL TRANSCRIPT

Music.

Welcome to UX Radio, the Podcast that generates collaborative discussion about information architecture, user experience and design.

Does user centered design at the forefront of ubiquitous computing, Big Data and dynamic visualization excite you? As the leader in predictive marketing analytics, according to Forrester Research, MarketShare is a fast growing start-up, building a world-class user experience team of interaction designers, front-end developers, visualization experts and user researchers.

If you have a strong background in application design and user experience, submit your resume at marketshare.com/careers. That’s marketshare.com/careers.

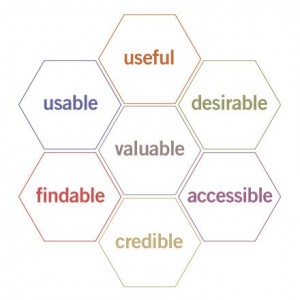

Introduction: Hi this is Lara and I’m your host for UX-radio. In this episode I’m talking with Peter Morville, president and founder of Semantic Studios, a leading information architecture and user-experience consulting firm. Peter is best known for helping to create the discipline of information architecture, and he serves as a passionate advocate for the critical roles that search and findability play in defining the user experience.

We talk about how he got started in Information Architecture and began to create a real connection between the physical organization of library information and the online world. In fact, this connection ultimately lead to the famous “Polar Bear Book,” by Peter and Louis Rosenfeld called Information Architecture for the World Wide Web. Here’s how he got started.

Peter: I was actually born in Manchester, England. But we moved to the US when I was 8 years old. So I learned to speak American real fast.

I mostly grew up in Connecticut. I went to college and did an English Literature degree. Graduated, had no idea what I wanted to do with my life. Went home and lived with mom and dad and started researching future careers. I came up with all kinds of crazy ideas from working in publishing to being a pharmaceutical sales rep, to being a hospital administrator. And every time my parents would just laugh at me.

And finally one day I was just wandering around inside a library and saw one of those little old books and it was called Careers in Library Science. And it had never even occurred to me that there were careers in library science.

But I looked through the book and at the same time I had been doing a lot of… I had been getting into computer programming and some of the early computer networks. CompuServ, Prodigy and AOL.

It just occurred to me that there was some connection between what had been happening in organizing information in libraries, physical information, and what was starting to happen in the online world.

So that’s where my interest in going to graduate school and library science came from. So I went to the University of Michigan and that’s kind of where it all started.

Lara: What led you to Michigan?

Peter: I looked at a number of different library school programs and their brochure was the most forward looking in terms of looking beyond the traditional library and how could we apply information organization and management practices to online or digital environments.

The funny thing was, that their marketing was ahead of reality. So when I got there, I found myself taking traditional courses in reference and cataloguing with professors who were 60, 70 years old. And there was definitely a moment of fear, terror there, where I thought I’ve come to the wrong place.

I managed to piece together the kind of education that I was looking for where I could have a good launch pad for doing something new.

Lara: And obviously there is value in those courses. But it’s amazing today what the program has become.

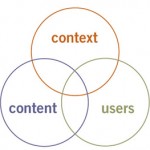

Peter: Yeah, it’s really become much more multi-disciplinary or inter-disciplinary, as has information architecture.

When we first started, one of our senses of mission was this idea of showing that principles of library science had value in the online environment. But very quickly, we recognized that there were lots of other fields and disciplines that had a lot of value to add as well. And we started learning about human computer interaction and usability testing. Then we started looking at ways that journalism and editorial skills could play into the work that we are doing.

So I think what has happened in academia with this multi-disciplinary approach has been mirrored in the world of practice, recognizing that there are all these places and areas where we can learn.

So I think what has happened in academia with this multi-disciplinary approach has been mirrored in the world of practice, recognizing that there are all these places and areas where we can learn.

Lara: So what was your next thing coming from that?

Peter: I met up with Lou Rosenfeld in the program and also one of our professors was Joe James who actually went on to found The Internet Public Library.

But the three of us, we spent a lot of time together, we played racquetball together. And we were some of the folks that were most interested in the internet at the time.

And so they had this company called Argus Associates and they convinced me after I graduated to join as the first real employee to try to take it from a hobby to a business.

I think if there had been larger companies that were offering the kind of work I wanted to do, I would’ve probably take that safer route. But there weren’t.

I’m not an entrepreneur by nature but I was kind of forced into that. And it was a wonderful experience. Over the period of 7 years, we really grew it from about 1 FTE (full-time employee) up to 40 people.

And it was a very exciting time and I got the opportunity to work on all kind of interesting projects for different clients. But then also to get a lot of management experience — what does it take to grow and manage a business? So it was a really fascinating experience.

Lara: So I can imagine since it was pretty small at the beginning, you were doing a lot of information architecture but probably a lot of the user experience as well. I’m sure there were many things you were doing.

Peter: When we first started, we didn’t even use the term information architecture. Even when we started using that term, up through writing the Polar Bear book in 1998, we still weren’t using the term user experience. But there was a phase where we were doing more what we thought as full service web design and we were involved in some of the coding and some of the visual design. And then we kind of decided we really wanted to specialize in what we were best at and find partners to collaborate with who had the design or development expertise.

Lara: So when did you have that moment when you and Lou were like, “We have to write this book and this is what we want to communicate with it.”

Peter: So Lou had been talking with this woman Lorrie LeJeune who worked at O’Reilly as an editor. And he had pitched her on the idea of a book on information architecture. And she heard him out but hadn’t been really excited about it.

But then she was going to a lot of the conferences and working the booth at conferences. And she came back to us and she said, “What’s interesting is I’ve been talking to a lot of people about what’s going on with websites.” And the term she used, she said, “I feel like I keep hearing again and again the same thing, and it’s the pain with no name.”

So there was a sense of frustration that something was missing but they didn’t know what to call it. And she was like, “I think that might be what you guys are calling information architecture.”

We wrote up a proposal and O’Reilly accepted it and it was interesting because what we heard back was, “Tim O’Reilly loved the idea about the book but he wasn’t so sure of the term information architecture.” So out attitude was, “Well, we are sticking with that term!”

So that was really exciting. At that period of time, our company was growing very rapidly. And we were working evenings and weekends to get the book done. And it was one of those moments in your life where it seems that everything is happening at once. And just getting to do a O’Reilly book at that point in time was so exhilarating.

Lara: It’s an amazing book and a lot of the talks here at the talks were on the new sphere of information architecture, what are your thoughts on that?

Peter: So in our community, over the years there has always been this tension around defining the damn thing. We even have our own hashtag, #DTDT.

And there has definitely been some negative side to that in terms of the political turn wars and trying to kind of say, my term is more important than your term.

I think there is a very positive side to that, that is coming out much more at this particular summit than ever before, which is first of all, a really important part of information architecture involves framing the challenges for our clients. Helping them to understand maybe this isn’t just about web strategy, maybe it’s more about cross channel experience strategy.

So instead of just thinking about a website, we’re thinking about a broader experience and a range of touch points.

So part of what we do is help people frame a problem or a challenge. But we also need to keep doing that for our own discipline.

Karl Fast gave a wonderful talk this morning where he said, the fact that we still need to define and frame and explain what we do, that’s actually the reason why we have a discipline. And it’s the same with other disciplines like physics that the reason why you have a discipline is to try to keep working through these really difficult issues about the core concepts and the boundary of the discipline.

So I think it’s wonderful that we are the 14th Information Architecture Summit and we are still wresting with these issues. I think that points to the fact that we have a very vibrant field that is still developing and maturing.

Lara: When you talk about re-framing the problem, and you’ve probably experienced this with corporations, sometimes it is challenging to help them understand how to re-frame that problem.

How have you learned to do that best?

Peter: I think part of it is… I’m always drawn to I guess what you might call systems thinking. Whenever someone says we need to fix this webpage, I think about how does this page relate to the other pages? And how do people get here in the first place?

And then I start looking at, well this isn’t so much an issue of how this page is designed, there are governance issues that are coming into play here. Who is responsible for measuring the performance of this page or site or experience?

So once you start asking all of those questions, it becomes a matter of trying to understand what’s really important, where are the levers? Where are you going to affect change in the organization?

And then what are the clearest ways of explaining that? And sometimes it’s a word or phrase or a way of capturing the problem. Sometimes it’s a visual representation, a map that helps people see things differently.

And sometimes it can be more about helping people to really see and feel the experience of users so that there is more of a…

So you can build empathy, here is what our customers are being forced to go through at the moment. And here is how we might start to fix that.

Lara: Sometimes you run into these political constraints. And I think those are some of the hardest to overcome.

Peter: So the Library of Congress story is a fun one because when I first started working there and I did an evaluation of their web presence and I was brutally honest and said there were some significant problems here, there was a point in time where my report was embargoed and they said, “We agree with you but this is too sensitive to share around the organization.”

But over the period of several months, that kind of critical review percolated up to the executive committee level and they made a courageous decision that we are going to change how we work on the web. And I was lucky enough to be brought back in to help with that.

So it’s actually a really nice example where an organization was willing to hear criticism and then make the changes necessary. I think that is rare. For every one of those, there are a lot of organizations where you can go in and tell them what’s wrong and they’ll thank you and they won’t do anything.

So that’s a really nice story of how coming in at sort of a middle level in the organization, there was a kind of willingness to listen and change.

Lara: Was your strongest relationship with the decision maker, or was it grassroots with all the smaller functions within?

Peter: It started out as more grassroots, which is partly why I didn’t have a huge sense of optimism that it was going to have the impact that it did. When it made its way up to the executive committee and they decided to really change how they work on the web, they appointed the chief of staff of the entire library to sort of chair a web governance board. So I worked closely with him and he provided the political leadership and protection to allow me to get my work done properly.

Lara: I think you can learn a lot from failure and you can also learn a lot from best practices.

I was really impressed with the National Cancer Institute and you got some nice awards along with that. What made that so successful?

Peter: The National Cancer Institute was an interesting experience for me because when I was brought in, there was already a fairly tight time-line in place. So I think I did all of that work within a 3-month time frame. And it felt rushed at the time. But I had this real sense of mission; it was a real honor to be working with that organization and its content.

When you sort of think about the use case of somebody who has just learned that they have cancer or a friend or family member has received that diagnosis and they are coming to the site and they are looking for answer or help or guidance or hope, the information architecture is so important to help them to find what they need in the least frustrating way possible.

I think part of the reason why it was such a big success is they had a really good team in place in terms of the technology side. They had a really good designer. And they had already worked through some of the difficult content strategy and content management issues. They had centralized ownership and management of some of the most important content that the institute publishes.

So I had a lot of good things to work with. And so it was kind of setup for success in that way.

Lara: When you said the content was centralized, who owned that? Was it the communications department? Marketing?

Peter: They had basically setup the web team… They were housed within the Office of Communications. And so the web team and the folks who were responsible for the content, were actually co-located in the same floor of the building. And they worked very closely together. So I think that really helped that project succeed.

Lara: I think it has been amazing to watch the search functionality grow into what it is today. So share with the audience a little bit about your experience, where it began, where it is today and where you think it is going.

Peter: In terms of search generally?

Lara: Yeah I think in general or if you want to dive down into faceted navigation or whatever.

Peter: Search is an interesting but very difficult area. I found it interesting enough and important enough that I decided to write a whole book about search. It’s difficult for a few reasons.

One is, for a lot of sites these days, people are going to Google and they are doing a pretty specific query and they are getting pretty close to the area they want to be on the site in the first place. Which to some degree is kind of marginalized the importance of site search.

There are some kinds of sites and applications where it’s important and others where it’s not as important as it used to be.

The other reason why it’s difficult is it’s such a huge challenge to design a search interface and a search system that really helps people find what they are looking for. The old joke is, it’s the stupid users; they are using the wrong key words.

It remains an extremely difficult and unsolved problem.

Google works wonderfully for certain kinds of queries. But I would say from my perspective, I think the limitations of Google are becoming more and more apparent each year. There is a lot of content that is not accessible via Google. A lot of times more commercial content is coming to the top of results.

One of my newer areas of interest, it’s an area I’ve been interested in ever since I went through library school. But I’m kind of starting to dig deeper into it. It kind of goes under the label of information literacy. And getting to questions of…

What I’m concerned about is most people don’t really know how to search well. And they don’t know how to evaluate the sources of information that they do find.

So they do a quick Google search and they blindly trust what they find. And I think it’s hugely problematic. And I know that in my life, having the benefit of having gone through library school, learned how to search really well and then spent my whole career on the web.

The fact that I’m really good at searching and at finding uniquely valuable sources of information, helps me understand what’s going on in the world, helps me make better decisions whether it’s what products to buy or whether or not to trust my doctor, what medicines to take.

I feel like information literacy makes my life better. And I feel that most people in society are really missing out on that. So that’s a gap I think that sort of exists in our education system that really needs to be filled somehow.

Lara: What solutions do you see in the education system to make that better?

Peter: I’ve been working with an organization the past several months called The Center for Inspired Teaching. And they do teacher professional development.

So I’ve gotten a bit more insight into how teachers are trained in the first place through the certification process and professional development. And I actually think a big part of the solution is teaching the teachers because they are ultimately the ones who are going to be working with the students.

If they don’t understand why it’s important to know how to search well and evaluate sources and if they aren’t encouraging their students to go out and search for themselves and be more critical consumers of information, I think it’s really hard to do it in any sort of add-on way.

So I think that ultimately teachers are at the center of this. And I don’t have an immediate plan on how to affect that but I think that they are central to dealing with this challenge.

Lara: Where does that take place? I would think maybe middle school? Maybe it’s earlier, I don’t know.

Peter: I think there is a place for it all the way through. And I’ve been helping our daughters with their homework and math is one of the areas where I end up helping quite a bit.

I was never particularly strong in math and I’ve forgotten most of what I knew anyway. So they asked me to help with a particular problem and I’ll say, “I don’t actually know how to do that, let’s go on Google and try to figure out how to do this.”

Sometimes they’ll tell me, “I already tried that. I went on Google and didn’t find it.” I’ll say, “Let’s do it anyway.” And I’m able to very quickly find something that helps us solve the problem.

So they go to Google but they don’t really know how to do the right search to find the answer they need.

So this is kind of the middle school age. So maybe middle school is where it really starts to come into play. They are getting on the internet, they are doing searches, but they don’t really have the skills to sort of flourish.

Lara: It seems that talking out loud with them while you are identifying the steps — “OK this is an advertisement, this is not going to give you the information you want. But this is a valuable source and you can trust this source because of XYZ.”

Peter: One of the interesting things that we talked about with the folks at the Center for Inspired Teaching because they have a number of principles that they try to encourage teacher’s to follow. And they have this idea of challenges.

So one of those challenges could be summed up in the notion of, don’t touch my pencil. So it’s the idea that as a teacher, when a student is having a hard time solving a problem, don’t pick up the pencil and solve it for them, help talk them through it in how to do it themselves.

And the same thing applies in an online environment where it’s actually better for me to say, “OK you sit down in front of the computer, let me talk you through it or have you try.” So to really get them to go through the process so they remember how to do it and how it worked.

I’ve actually been working on that myself a little bit. Instead of solving the problem for them, having them go through the process themselves.

Lara: It’s that tell, show, do, measure kind of thing. When they actually do it, well for many of us, we absorb it more because we are having the experience first hand.

Peter: Absolutely. I think that’s an interesting dimension from an information architect perspective. Organizing information for access is one way we can help people learn and understand and make decisions. But there is all this interesting educational theory and knowledge about how people learn and how to teach, that many of us are ignorant of.

That’s a whole other domain that we can draw lessons from and try to figure out how can we improve our digital products and services in a way to help people move beyond just getting the information, to trying things, experiencing things and learning that way.

Lara: Do you use Google or do you use something else to do your searches? What is your process?

Peter: I use Google all the time like everybody. But I feel like we are missing out…

One of my frustrations is the walls around academia. The fact that if you are within a University environment and you have access to all these wonderful journals, databases, you have access to the scholarly record.

And people in those environments take it for granted. But you step outside that wall and you have almost no access to that content. And I think that’s a problem that has been getting worse, not better.

10 years ago you could walk into most academic libraries and access all of that content. You could go to the print journal; you could go to the books. Our Universities were very open.

Nowadays, more and more of that is being digitized and unless you’ve got the login and password, you aren’t getting to that stuff.

I think that’s a really sad trend and I feel that we have to find some way… Some of this is happening within the open access movement. But we still don’t have… Google Scholar has some value but again unless you are in one of those communities, you cannot actually access the full text of many of the articles.

So we are really missing out on widespread access to the scholarly record.

Lara: Do you think due to just the economics of the whole thing, they are trying to make some money on the amazing content that they have?

Peter: We won’t go too far into all the problems with the journal publishers who are making crazy amount of profits and clinging onto that model of publishing and sort of a monopoly situation. But I think as a society, it’s in the best interest of our society to figure out how to free up more of that information.

And it’s happening in bits and pieces now with professors putting their articles out on the web whether it’s legal or not, they just feel strongly compelled to make their content available.

But having it be available doesn’t mean it’s findable. We don’t have an easy way to search across all of that content in any kind of an efficient and easy way.

Lara: Last year I took a course, a MOOC (Massive Open Online Course) course through Coursera, it was Stanford’s HCI class with Scott Klemmer. And it was such a great experience and it was one of the first and we had the peer-to-peer evaluation. And they were doing a lot of testing because they were just getting it started.

But it was so great to be part of that. And I was so thrilled that it was available to anyone that was interested in the topic.

Peter: Yeah, so there are a couple thoughts I have about MOOCs as I think they are a fascinating phenomenon. Actually I wrote an article recently called Architects of Learning where I talked a little bit about this.

MOOCs actually have an opportunity to maybe try to dig into this problem because a lot of people who are taking that course, are not within an academic environment. So the question becomes, how are the MOOCs going to provide access to the scholarly content that is relevant to that course.

I think that’s a challenge and maybe a big opportunity for the MOOCs to try to solve.

The other thing that’s interesting to me, I think we are still really wrestling with… There is obvious value of making this kind of education very open and available on a wide basis and for free and so forth.

At the same time, there is so much value in being physically together and having a teacher who can really respond to you one on one.

So it’s a very interesting period in education where there is a lot of hype. If you just kind of pay attention to the hype, you think it’s all changing, people have the idea. I think the technology is only a piece of it.

The best book I read on this topic was by Clayton Christensen and I think his book is called Disrupting Class.

And he argues that compared to the traditional classroom experience, MOOCs kind of suck. But they sort of suck in the same way that the early Apple computer sucked relative to the IBM mainframe.

There is something there that is the seed for true disruptive change in the coming decade or so.

I’m fascinated by what’s going on there and it’ll be interesting to see what happens.

Lara: Yeah, it was an interesting experiment and it was nice that they offered the two different tracks. One was like, listen to the videos, take the quiz. And the other was much more immersive in actually designing the app by the end of the program.

And then you had the peer to peer but they weren’t necessarily all skilled in a heuristic review. So you have some like, that’s pretty good. And then some that were very thorough and went through a set of standards.

So I think there is certainly a lot to iron out. So what do see as the next big thing?

Peter: There have a lot of ups and downs in the perception of information architecture over the years and at the summits. And I felt that while within the community, there are these constant sense of shifts. The big picture just in the world of work has been the need for information architecture has been growing and growing.

On my consulting side, I just keep having really interesting work with great clients and so I’m continuing to do that.

I feel like I’m kind of at the point where, before too long I’m going to want to dig into working on a new book. And even just at the Summit I’ve playing over ideas of what that means, what it would be about, how to frame it.

During Karl’s talk this morning, he sort of mentioned the challenges not of big data but of small data. And I was thinking the area that kind of interests me, you can almost call it personal information architecture which is helping people with the information architecture of their personal lives and how they learn and make decisions.

So you can talk about it in that small way but you can also talk about it in a big way, which is, what’s the information architecture of society? What are all of our structures, frameworks and processes for creating and sharing knowledge and for establishing authority and trust.

How do we know who to trust, what information to trust?

That’s an area that’s really interesting to me that is well outside the normal business information architecture world. That’s kind of where I am being tugged at the moment.

Lara: That’s wonderful. I look forward to that.

Well thank you so much for your time today, I really appreciate it so much.

Peter: Sure, I enjoyed talking with you.

[speaker]# UX Radio is produced by Lara Fedoroff. If you want more UX Radio, you can subscribe to our free Podcast on iTunes. Or go to UX-Radio.com where you’ll find Podcasts, resources and more!

MORE ABOUT PETER

Peter Morville renown author, speaker, and teacher of information architecture is best known for creating the field of information architecture through his work including his best-selling books, Information Architecture for the World Wide Web, Ambient Findability and Search Patterns. He has provided successful solutions for some of the world’s most complex, challenging, and innovative environments including AT&T, National Cancer Institute, Macy’s, Ford, Proctor & Gamble, and the list goes on. His work on information architecture and user experience has been covered by BusinessWeek, The Economist, Fortune, NPR, and the Wall Street Journal. Peter lives in Ann Arbor, Michigan with his wife, two daughters, and a dog name Knowsy. Be sure to visit his blog at findability.org.

Connect with Peter here:

- @morville

- Semanticstudios.com including presentations and publications

- Peter blogs at findability.org

- A brief overview of Understanding Information Architecture

- Information Architecture 2014 IA Summit Closing Plenary

Semantic Studios is an information architecture and user experience consulting firm led by Peter Morville. They help clients around the world to create better web sites, intranets, and interactive products and services.

Peter is the author of several books, including Search Patterns (co-created with Jeff Callender), Ambient Findability, and the best-selling Information Architecture for the World Wide Web (with Louis Rosenfeld).

As Chief Executive Officer of Argus Associates (1994-2001), Peter helped build one of the world’s most respected information architecture firms, serving clients such as AT&T, Barron’s, HP, IBM, L.L.Bean, Microsoft, Procter & Gamble, Vanguard and the Weather Channel. He has also worked with libraries, universities, nonprofits and foundations.

Peter is a founder and past president of the IA Institute and has served on the ASIS&T board of directors and as an advisor for the Encyclopedia of Library and Information Sciences and the Z39.19 standard. He now serves on the advisory boards of the Journal of IA, Rosenfeld Media, Interaction-Design.org, Project Information Literacy, and as a member of the SJSU SLIS international advisory council. Peter holds an advanced degree in library and information science from the University of Michigan’s School of Information, where he has also served on the faculty.

RESOURCES & REFERENCES

- Semanticstudios.com

- Argus Center for Information Architecture ACIA

- Jess McMullen

- Information Architecture for the World Wide Web: Designing Large-Scale Web Sites by Peter Morville and Louis Rosenfeld, O’Reilly, 2008